1950 -1959

Life at 21 Command workshops was rosy, by and large. Burscough, while small, had two railway stations. The main line, North - South line which had a station just outside our workshop gate and a smaller one about a ½ mile away on East – West line which terminated at the sea side resort town of Blackpool.

This was a favorite destination at weekends. Besides the famous tower, it had beaches, amusement arcades and things like that and of course any number of young girls on holiday!! Ah memories.

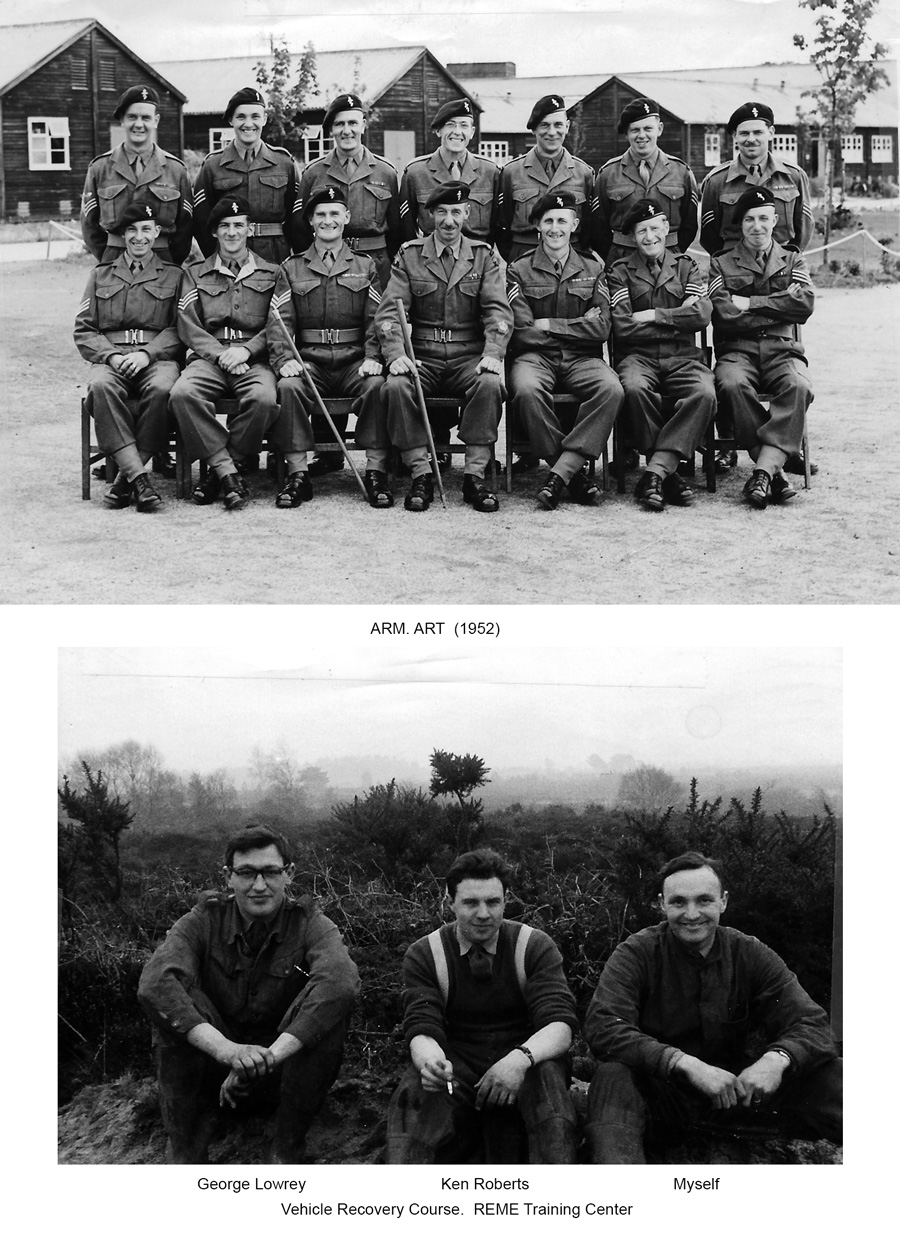

I remember once while in camp, wondering whether I should be doing something more exciting. I applied to join the Airborne section of R.E.M.E.

A few weeks after submitting this application, I was in Blackpool and went up the tower, looked down at those little ants walking about down there and thought “what have I done?” Fortunately, a few weeks later I found out that I was in a restricted trade and couldn’t apply. Big sigh of relief.

My brother, Richard sent them the same query, but his trade Gun and General Fitter was not restricted as he was selected. He told me later that he never got over the fright of jumping out of an airplane.

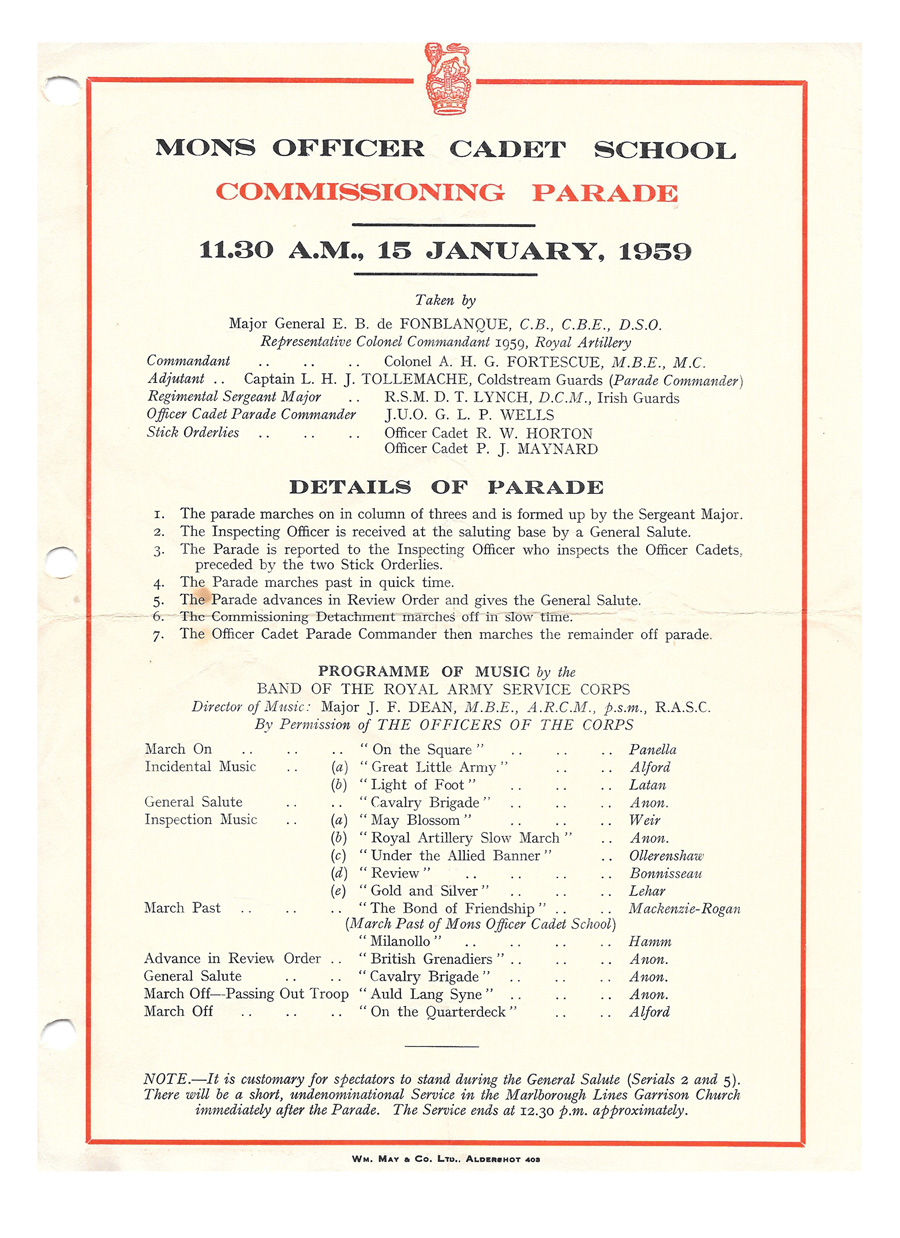

As I had reached the top level in my trade, any further progress would require applying to be an Armament Artificer, or Arm Art for short.

The name is a hangover from the days of cannons, horses and sabers. Every regiment would have its Armament Artificer. Minimum rank was Staff Sergeant and he was, effectively, ‘god’ in the regiment as he took care of all the guns, carriages and any other wheeled transportation.

Obviously, as the Army changed, so the equipment got more complex until, as it is now, we have radar, radios, instruments, tanks, armored cars, motor cycles and a whole heap more. No one man could possibly cover it all.

The individual trades now had their own Artificers. So, I applied to take the Artificer instruments test. This is a two-week test in Arborfield and there they hammer you day in, day out. Not so much on your trade but on Military training intelligence tests, leadership and problem solving.

After two weeks, six days a week, it can be a grind and the usual failure rate is 50% is not to reassuring.

However, all things end and in due course I marched in to the final board consisting of 3 officers and awaited with trepidation.

“Stand at ease”, says the board leader, “relax, you have passed”

“But”, says he, “we think you are in the wrong trade”

I must have expressed my surprise but then he informs be that, based on my results, I should have been an electrical engineer.

He then tells me that there was a new trade opening called Electronic Control Equipment or E.C.E for short and a course will be forming up in Arborfield in about 3 months but in the interim we would be attached to a Leading Artisan Sergeant course which was starting straight away. This course was designed for three draftees who had opted to go to University rather than getting drafted at 18. (Hoping the draft would be over by the time they graduated) However, being University trained, after basic training, they were put in front of a war office selection board (W.O.S.B), where many of them failed. However, as R.E.M.E worked on the principle that anyone with a degree could be taught, they finished up at the 5 training battalion in where they got a short session on electrical theory and then were trained on the equipment. Three of us “wrong trade” appointee’s Dicky Yarlup, Jack Devlin and I joined this L.A.S.S course, what a shock of course, all of the draftees knew their electrical engineering, ac and dc theory, ac and dc machines and the mathematics to cover it all. We essentially, started from scratch and had to work our little butts off. What a course that was!

In our course, the Arm Art course we were scheduled for formed up and we joined them and did all the same engineering again. However, this time it was easy, we had learned so much from our draftee colleagues.

In 1952 we finished the course and I was selected to stay on as an instructor. This was a great way to consolidate all my training.

The equipment we covered was all the control systems used on the anti-aircraft guns, (mostly hydraulic) which tracked the planes and calculated range, elevation, beaming and time of flight, the radars which fed range, elevation and beaming to the predictors. At this time there were two electronic predictors, the number 10, which was dc operated and the number 11, which was ac. An earlier predictor, the Vickers, was all mechanical, was still around but was being phased out.

We also covered searchlights, gun stabilizers and tanks.

At this time, 1952, I was wondering whether any of our training had any relevance to a civilian career. This thought came up as I remember a university man on the L.A.S.S courses had said it was about Bachelor’s Degree level. To this end, another one of my colleagues and I drove into Reading Technical College, with a complete breakdown of the course material we were giving at 5 Training Battalion.

He was most dismissive and said it had no relevance to the courses he supervised.

This was a bit of a setback but rather then taking it at face value, my colleague and I went up to Twickingham, about 20 miles away on the outskirts of London. There we had an interview with the principal, a Mr. Webb, who was most gracious, took all our curriculum papers and said he would check with the Institute of Electrical Engineers (I.E.E) as they set and marked the exams for the Ordinary National Certificate (O.N.C) and the Higher National Certificate. These exams were common to all Technical Colleges and Universities in the country and were required for a bachelor’s Degree in the University.

Imagine our delight when he contacted us a few weeks later to say that our training would allow us to miss the first year of the O.M.C, if we took the machine drawing exam for the first year.

While we didn’t instruct on machine drawing, it was one of the classes we took in Boys Service, so it was no problem. With a couple more instructors interested, the Colonel of 5 Training Battalion very kindly agreed to provide railway travel warrants for three nights a week up to Twickingham for us all.

After two years we took and passed the O.N.C exams which now allowed us to proceed on to the H.M.C. By this time, we had been joined by several instructors from our sister training battalion, 3 Training Battalion which specializes in telecommunications. So about 7 or 8 of us now commuted up to Twickingham. The principal and staff there were tickled pink to have us we consistently passed all the exams and completed all the courses. The normal failure and noncompletion of the regular students was up near 50% so this was a great boost for the college.

In fact, one of the instructors from 3 Battalion took to I.E.E.E prize that year for the highest marks in the country for the H.N.C. A wonderful achievement.

After I finished my courses I heard over the grapevine that the Principal of Reading Technical College made a special presentation to the two Colonels to persuade them to send their students to Reading instead of Twickingham. It made me sense of course, as Reading was only seven miles away but it was obvious why he wanted us.

To obtain I.E.E membership, one had to take more additional courses and in 1954, I obtained endorsements in Physics. Higher Math, Engines and Mechanical Engineering, all taken at Twickingham. I needed one more, which I took, in 1955 from the Farmborogh (R.A.E) Technical College in Control Systems.

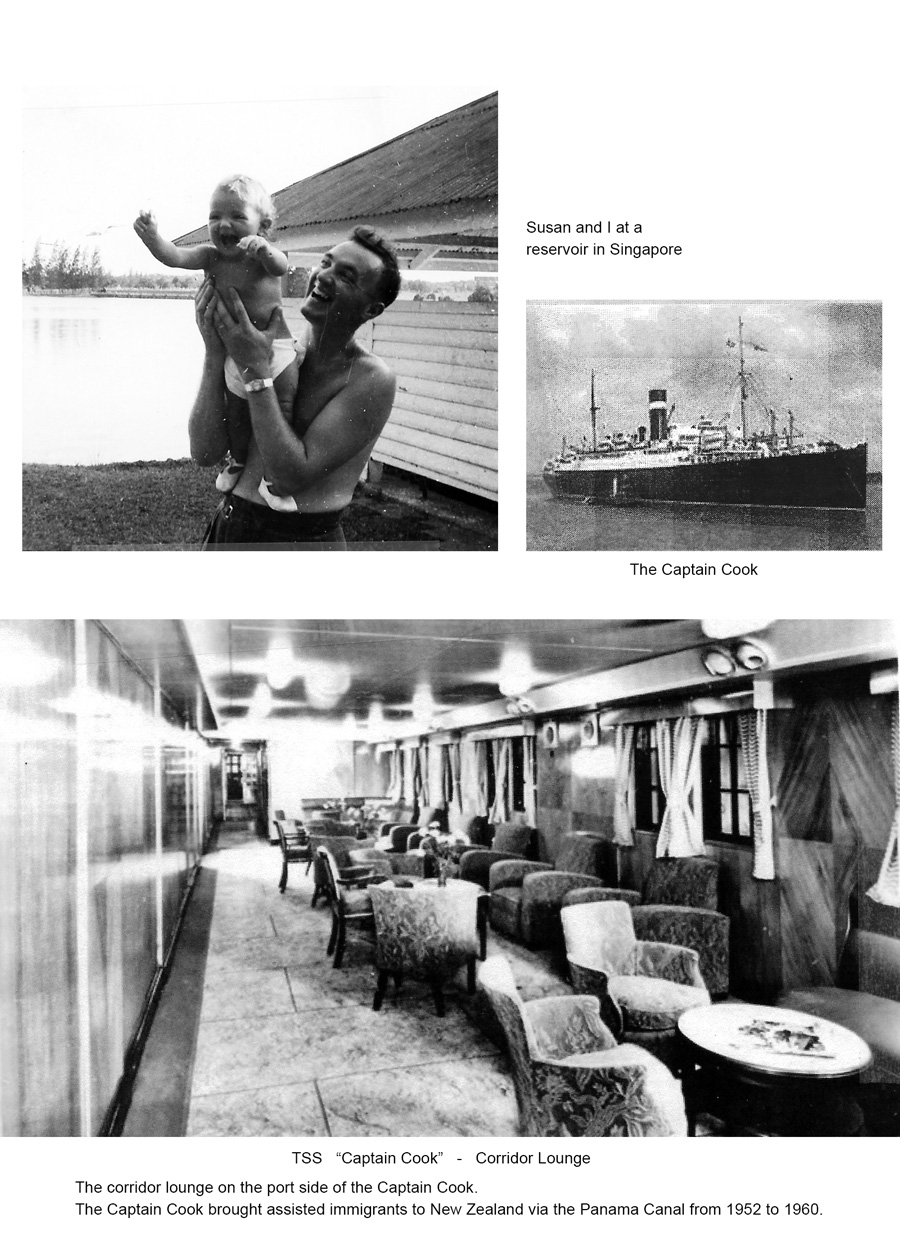

I just managed to finish this course before I was posted to Singapore. I had already married my sweetheart Jeannie in 1955 and welcomed our beautiful daughter Susan in 1956, so all three of us set off on a new adventure.

At this time, they were flying replacements in old, noisy, propjet aircraft and it took four days and three nights to Singapore.

London to Brindisi to Beirut to Bahrain to Karachi to Delhi to Calcutta to Singapore.

We had two nights in hotels in Karachi and Calcutta. Flew overnight from Beirut to Karachi. Susan was spoilt rotten by the stewardesses and we had her in a cot fixed to the wall in front of our seats, but the vibration kept her asleep for most of the journey.

I had been posted to the R.E.M.E Training Centre, Far East and were settled into a civilian rental bungalow in an estate called Serangoon Garden Estate about 10 miles from the training center. We were picked up by truck every morning and dropped back off every evening.

Singapore was a fun place with lots to see and do. Besides the beaches one could also picnic at one of the reservoirs in the middle of the island. There was a bustling social life between all the Brits. I was in charge of the electrical section and taught the British and the Malay Army. The Malay Army consisted of both indigenous Malay and Chinese immigrants.

I taught electrical theory, both as and dc, electrical machines (ac and dc), vehicle electrical systems and battery maintenance. Essentially, I lectured 8 hours a day, assisted by two British civilians.

Hong Kong, on the Chinese mainland was part of the command and, instead of sending their electrical people down to us for lectures and trade testing, we would send a small group up to Hong Kong. They usually flew up there on an R.A.F transport aircraft. No seats to sit on. However, in 1957 there was a cyclone threatening the area, so the flights were cancelled. Instead we were sent on a troop ship which had docked in Singapore and was heading for Hong Kong.

We had two great weeks in Hong Kong. Thoroughly explored the main island and as we were stationed at a Base Workshop at the mainland and got a great introduction to the congestion that existed there. Mainland Chinese used to come across the boarder in the thousands to try to leave the destitution of Communist China. We got the opportunity to go out with a Gurkha Platoon who were going up to the western end of the boarder. We went up by launch and the platoon disembarked and started off on a hike right across the peninsular. It would take a day or so and they would be picked up on the Eastern end. Obviously, a daily patrol wouldn’t keep out the immigrants, but it served to present that a boarder existed.

While there, we made the acquaintance of a Sergeant in the machine shop who was a scuba enthusiast. Scuba diving was in its infancy then, but he made up some diving gear to allow us to swim underwater. He took us up to a place called Clearwater Bay. A beautiful place, well named. The water was crystal clear and about 20 feet deep, packed with fish. He gave us a short lesson on what to do, gave us some led filled belts to cancel out buoyancy and sent me in. What a revelation! It was just as though we were fish. Unfortunately, at some point in the adventure, my breathing gear stopped working and all I could get was water.

Frantically trying to swim back to the surface I was certain I was going to drown and only by dumping the lead belt was I able to make it back to the surface. Ah excitement!

We returned to Singapore by plane this time, a rousing ride.

In Feb 1957 I was notified that the I.E.E had confirmed my exam results and that I was non-grad I.E.E. I also confirmed that any higher grading to A.M.I.E.E could only be as an officer in the Army. I therefore applied for a short service commission, got recommendation from two Colonels (one in the Royal Engineers, who apparently had served with Dad).

Commissioned applicants had to attend a War Office Selection Board (W.O.S.B) which was based in England. So, in due course, I set off by plane for England, leaving Jeannie and Susan behind, because if I failed I would have to come back to complete my tour in Singapore.

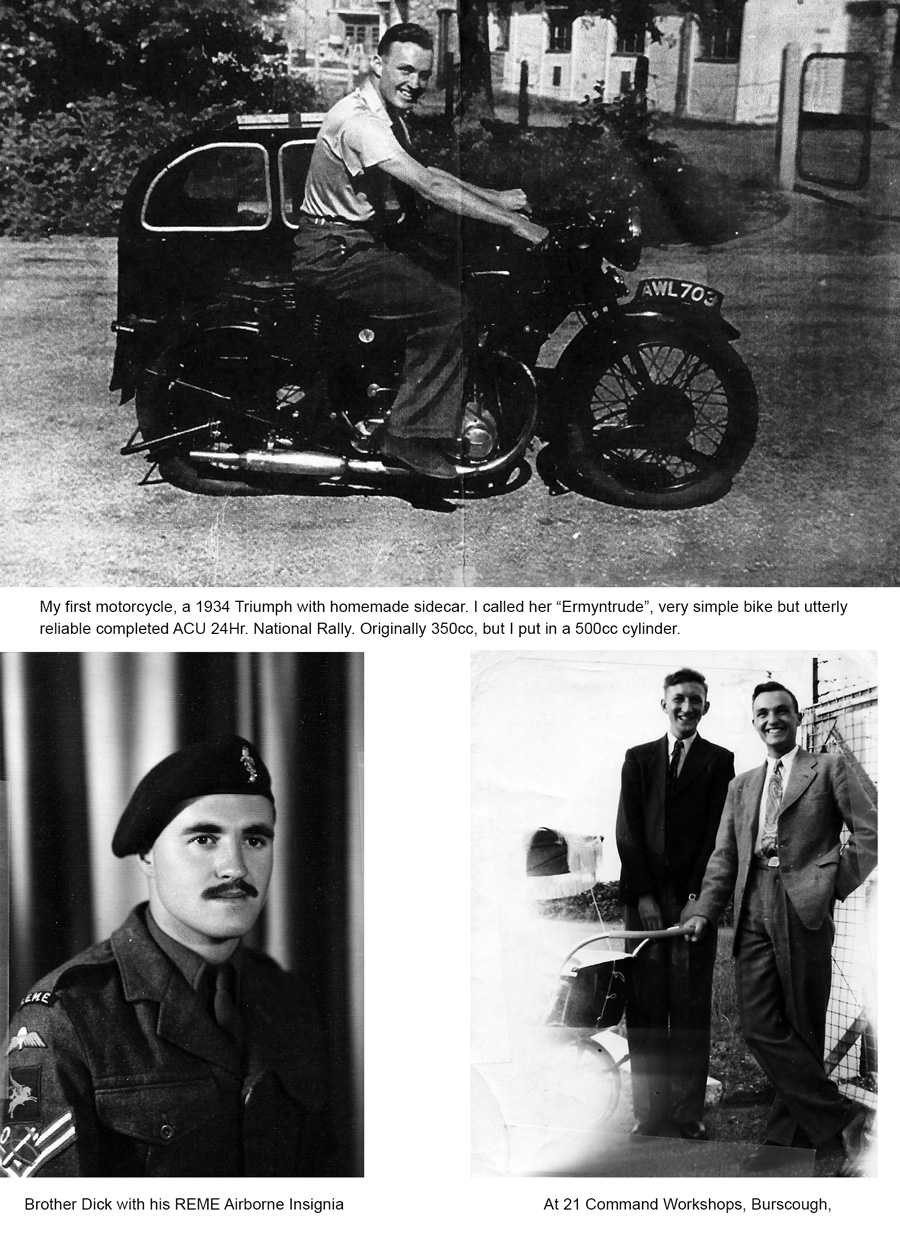

As it was, I attended W.O.S.B., passed and sent a telegram to Jeannie to say “Passed, start packing”. At which point everything went downhill. The Suez crisis came up. France and Britain invaded Egypt to seize the Suez Canal. All flights were stopped, and Jeannie and Susan finally came home on a requisitioned troopship, the Captain Cook, an emigrant ship taking Britons to Australia and New Zealand.

I cooled me heals at the R.E.M.E Depot for a few months, awaiting instructions to attend the officers school. Finally got instructions to report in September 1959. At that time, I had disembarkation leave and privilege leave piled up, so I took off home to my mother for 2 whole months. Obviously, I couldn’t hang around for that long, so I took a job at Edgar’s Dairy in New Milton, initially as a bottle washer, finishing 8 bottles at a time into a crate which then went into a bottle washing machine. However, I found that I had some expertise in repairing the bottle washing machine and then any other machine which broke down. In addition, I drove the dairy truck around stops in the town and beyond. After a month of this, my mother wanted some painting done and I gave in my notice. It didn’t last long though within a week, Mr. Edgar was knocking on our kitchen door “could I come back”. So, I went back for another 2 weeks.

Got notification that the Captain Cook would be docking in Southampton on the evening before I was due back in camp. I went down to the docks and spoke to the senior officers on the ship. Since Jeannie had no large luggage and only a couple of suit cases she was given permission to disembark that evening while all the rest had to wait until the next day.

Next day I reported back to camp and from there to officer’s school in Aldershot. A three-month grind to say the least. I was about the oldest in the squad but enjoyed the comradery with the lads. Some stuff was easy, because of my previous service, but a lot was new. Finished up with three days of exercises on the Brecon Beacons in South Wales. Boy was it cold there. Ice on all of the water and hard frosts every night. I appreciated what the invading troops endured in Europe in 1945. At least our trenches only had water and ice in them, we didn’t have to worry about being shot at or shelled.

We had one cadet in our squad called Drew (right hand side, second row of our squad photo) who was a ballet dancer from the Festival Ballet in London. Jeepers, was he agile, two feet (or more) higher than us when jumping in the gym. At our passing out parade, my mum and dad came up, he invited all the girl dancers from the ballet. When they trooped in to the bleachers later in the gym, they caused quite a stir. They don’t walk, they bounced!! They must have been 8 or 9 of them.

After graduation we were posted back to our final depot, for three of us, it was back to R.E.M.E.

Here we went through another officer’s course very similar to what I had done in a junior leader course, but much more refined. We get to pull tanks out of holes in vehicle recovery section.

In Feb 1959 we finished, and I was posted to 21 Light Antiaircraft Regiment as second in command to a light aid detachment attached to the regiment. The L.A.D was commanded by a Major Frater and was about 130 men strong.

We took care of the vehicles, instruments and wheeled transportation. Maintenance on the light anti-aircraft guns (B.O.F.R.S.) was done by the R.A, but we could provide any small machine work or welding as required. It didn’t last too long. In March the regiment and us, were ordered to go to a place called Omagh in Northern Ireland for six weeks to replace a regiment which was going to Germany. The replacement regiment from Germany would not arrive for six weeks.

In the interim we would provide patrols along the boarder and security in the town. We drove up from Pembroke Dock in a convoy, so we had all of our own vehicles. However, as all wives and children had been left behind in Pembroke, the C.O. was very generous in providing weekend leaves for us married officers and I was able to get back to Pembroke Dock in March.

The stay in Ireland was uneventful but I did manage to take some of the lads up to Belfast for a weekend photography course at the University of Belfast. I don’t think the lads were that interested in photography, but it did give them a weekend out of Omagh.

While there we bunked at the barracks occupied by the 17/21 Lancers, a cavalry regiment, now converted to armored cars.

I was bunking in a room normally occupied by a major on leave. It was a wonderful chance to explore their officers mess, with the Regimental Standards all around the room. Lots with bullet holes and burn marks, what a sight. It gave me an in sight into the Regimental Pride that these old established regiments had.

R.E.M.E didn’t exist before World War II and, in any case, we never serve for long with any one establishment.

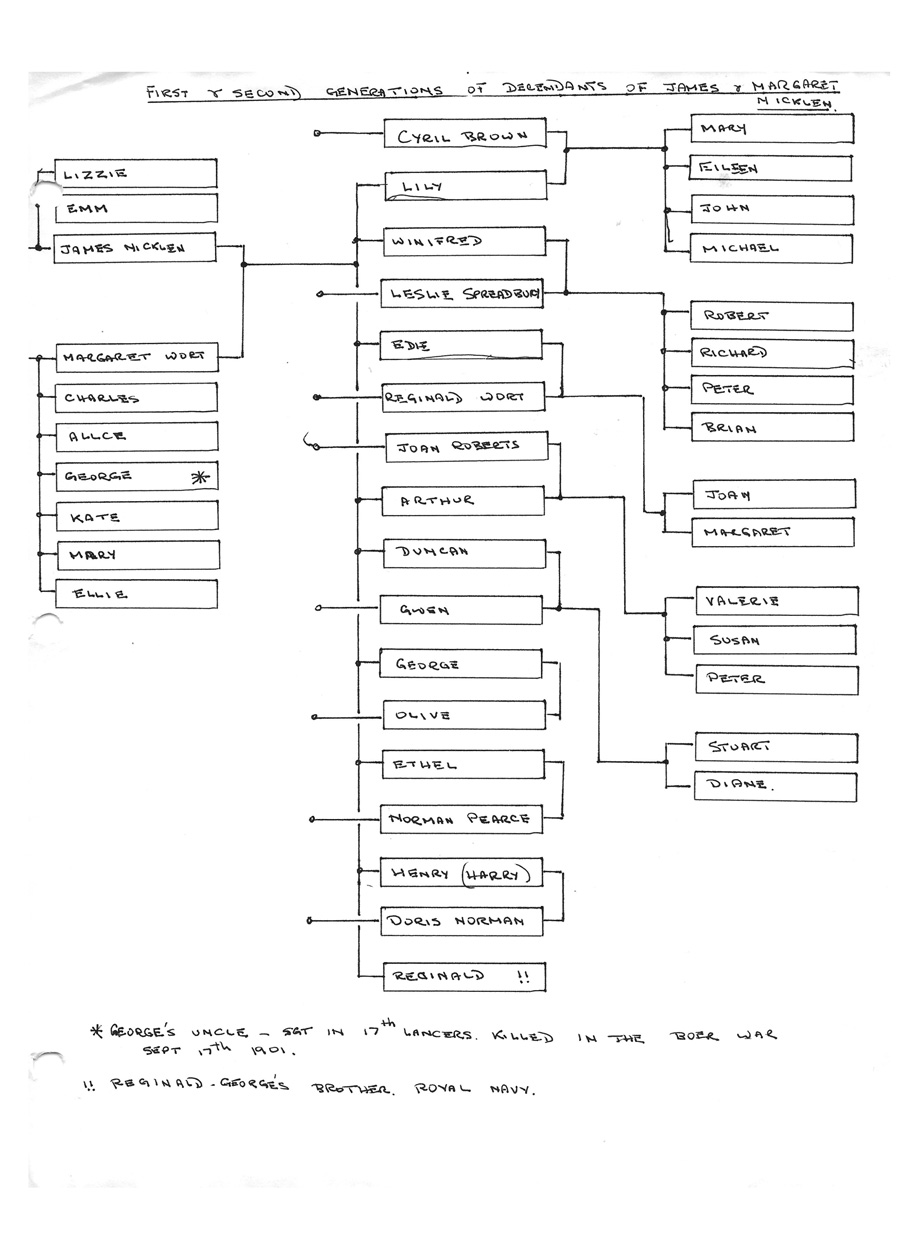

At this point in time I didn’t know about George, brother of my grandmother Nicklen. Apparently, he was in the 17th Lancers (then with horses) in the Boer War and was killed in South Africa. If I had only known, I could have been more thorough in my examination.

At the end of 1959 I was posted to the school of antiaircraft artillery as second in Command to their somewhat larger L.A.D. The school was stationed at Manorbier, about 15 miles back up the coast from Llanion Barracks. Here antiaircraft regiments of R.A. came to fire their guns at aircraft towed out across the Bristol Channel.

Gun calibers vary from light 40mm Bofors to 3.7 inch. They had radar equipment so that the L.A.D. had to service electronics equipment as well as predictors which probably prompted my posting.

(L – R) Brian, Peter, Jeannie, Me, Mum Winifred and Richard

1950 -1959