1940 -1949

On our arrival in Singapore, we were installed in the married quarters in a district called Changi. We have very few photographs of our first 12 years. All the photos up to then were lost when we evacuated. Any shown have been from pictures that were sent home.

We were enrolled at the local army school. I can only remember that there were two teachers, a head mistress and a headmaster husband and wife, named Martin. I suppose I learned something there, but I can’t remember much. Mum taught me at home, I think she always wanted to be a teacher, but she made sure that we all could read before infants’ school. I was an avid reader, anything I could get my hands on. My earliest memories were of a history book, given to me by Uncle Tim (husband of Aunt Vera, Dads Sister). It was the “History of England”, a hard read with it’s very small print and copious footnotes and side notes, but it had the effect on me, in that I developed a love for thinking and I can still recall one footnote which described in detail, the execution of King Charles 1st, including how many strokes it took to sever his head, by which time the observing crowd were so upset by the cruel parody that they were shouting for the executioners head. He had to be escorted from the scene by the guards.

Life in pre-war Singapore was idealistic, while it was hot and humid, being a few degrees off the equator, it meant an early start and finish at school. As memory serves it was 7 am to 1 pm. The afternoons were for us to be enjoyed. Most days we spent at the Pagar, a fenced off section of Changi beach. I was taught to swim by Mrs. Martin when we finished early one day and the whole class went down to the Pagar.

She observed me paddling and not going all the way in, called me over to her, took me a bit further out, putting out her arms and told me to lie across them. Then she said, “kick and move your arms”, so I started doing a dog paddle and she took her arms away and I was paddling, wonderful!! I learnt freestyle next and I was away. Have always enjoyed swimming and must admit that I have had many pleasant hours just floating on my back.

School discipline was strictly enforced by Mr. Martin and his whipping cane. I had my share as I sometimes can’t avoid talking in class. Our school uniform was a white shirt and khaki shorts. It was always the same “bend over boy”. The shorts were tight over your bottom, then Mr. Martin would give his whipping, rattan cane a couple of swishes and then lay on six of the best. Boy did it sting, you would go back to your desk, raise your bottom so that the sore part was in the space between the back and the seat of the desk. I didn’t dare tell Dad afterwards, he would have given me a cuff as well.

Dad was a strict disciplinarian, “boys should be seen and not heard” was the dictum he was brought up with, but he was always fair.

I remember when I had my first bike and was coming down a steep hill far too fast and had to make a sharp right turn at the bottom of the hill. Too fast and too far in the wrong lane and found I was heading right for a truck in the oncoming lane. The next moment I was lying in the road, face down and pinned by the trucks front tire. The truck backed off and I got up and staggered to the side of the road. My shorts and underpants were hanging around me like a skirt. It wasn’t until then that I lifted my skirt and found I was looking at a big hole in my right groin. Something had gone in at the hip, gouged out all the fat, skin and muscle in a hole about 5 inches in diameter. Amazingly enough it had not penetrated the membrane that enclosed the bowels, though I could see them moving, a most un-nerving sight. Fortunately, the accident took place right outside of an army office and it wasn’t long before I was in the local military hospital. The only boy in a ward full of men.

The next few weeks were a little traumatic. I had to lie on my back with a cage over my hips to keep the bed clothes off my pelvic area. Every day the staff would come in, lift off my scab and put hydrogen peroxide all around the edges of the wound.

This used to bubble and hiss and sting, but amazingly, slowly and steadily, new tissue grew in from the edges and after six weeks it was completely re-grown. A bit marbled of course, but complete.

Life was fairly uneventful through 1940. We knew of course, about the war in Europe and Mum and Dad were of course very worried about their families. It wasn’t until mid-1941 that things started heating up. My Dad was involved in the setting up the number One Bomb Disposal Unit in Singapore. By this time, of course, plenty of experience had been gained in Britain on the art of bomb disposal and this was quickly disseminating around all Royal Engineering establishments.

At the end of 1941, Singapore itself was bombed and I remember standing outside our quarters in Changi on the opposite side of the island, with Dad, watching the flashes and Dad saying “It looks like the balloon has gone up” After that he was gone for long periods at a time, apparently defusing unexploded bombs. He would come home at intervals for a change of clothes and a meal while Mum took care of the boys.

I remember him telling me about one bomb which had come through the roof of a building, had split open and coated everything with what is called “Yellow Picnic Explosive”. It had apparently hit a bed but didn’t go through and had just disappeared. They searched the room for the bomb and then someone opened a wardrobe and there was the bomb. It had apparently bounced off the bed into the open wardrobe and the door closed behind it.

In Jan of 1942, military families were evacuated on a requisitioned Cunard Line ship called the Samana.

The ship was tightly packed, not only with families but also with the survivors of the “Repulse” and “Prince of Wales” battleships which had been sunk by a Japanese carrier aircraft on Dec 10, 1941.

We were not too heavily laden as we had only two suitcases for Mum and us four boys. Everything we had accumulated in 22 years as a family was lost.

The ship was unescorted and came across the Indian Ocean to Durban and Cape Town in South Africa. The ship then made a big sweep out into the Atlantic Ocean up and around Iceland to miss the U-boat packs in the English Channel and Bay of Biscay and then south into the Irish Sea between Scotland and Ireland, arriving in late Feb of 1942 in Liverpool. We essentially only had shirts and shorts and really felt the cold. However, we finally took a train down to London, crossed London on the Underground and then took another train to Woking in Surrey.

Particularly on the second train we passed great areas of bombed houses as we passed through the London suburbs.

My mum’s parents lived in Chobham, a small village about 5 miles from Woking. Grand Dad and Grand Ma Nicklen lived in a small 3 bed room duplex, but they made us welcome and even though my Uncle George and Aunt Ethel were also living there, somehow or another we finally finished up in one bedroom. There was four of us in one bed while Brian, the youngest just fitted into the bottom drawer of a chest of draws.

Dick, Peter and I were enrolled in the village school and it was at this point that a Ms. White came into our lives. During the war, ladies and gentlemen who were too old or infirm to work in factories volunteered in the social services. Ms. White heard about us and came to visit. What she sees horrifies here and spoke to a friend of hers, the Countess of Lauderdale, in Scotland.

The Countess had lost one of her estate workers to conscription and had an empty ½ duplex we could rent. So that Autumn we left Kings Cross Station in London with the overnight train to Edinburgh. We disembarked at Wayside Halt, about 30 miles from Edinburgh at about 7 in the morning and we were met by the Countess in her Rolls Royce and driven to her home, Thirlestane Castle in Lauder.

We were given breakfast and then we were driven down to Wyndhead Cottage in Lander.

Apparently, a girl’s school in Edinburgh had their school requisitioned by the army and the girl’s school had been moved to the castle. While it was normally a girl’s school, apparently some of the local big wigs young sons had been enrolled as well. Initially the Countess had thought of enrolling us there but on seeing us had decided against it. Was I relieved, a girl’s school!

In any event we were enrolled in the village school, what a shock that was. I had never realized how pitiful I was compared to the Scottish education system. It was miles better than the English equivalent and light years ahead of the army school. However, we did have one advantage. We had a much broader education due to our travels. However, my reading habits really paid off in that while my English grammar knowledge was pitiful, I always knew what was wrong with a paragraph or sentence, whatever it was it impressed the village headmaster.

In Scotland they take an Eleven Plus exam which decides whether a student goes on to secondary school (grammar), technical school, (crafts) or stay on at the village school up to age 15.

Somehow the headmaster made a special request to the school board and I was awarded a scholarship to attend the high school in Duns, which was the chief town in Berwickshire, about 35 miles away. This entailed a 7-mile taxi ride to the nearest railway station, Earlstown, a 20 mile ride by train to Duns and a 2 mile walk to the high school. I did this trip for 3 years.

It was while I was with this school that I had my second experience of anti-English. We had another boy in the class who came from Berwick on Tweed. His name was Lyle. The history master was an anglo- phobe and whenever a suitable point came up in his lectures, he would make Lyle and me stand up and we would be the Earl De Spreadbury and Baron De Lyle, and he would make snide remarks about us. All we could do was fume inside as they were very quick with the “Tawse”, a heavy leather belt across your hands. A belting with that and you couldn’t hold a pen or pencil for a couple of hours.

That was bad enough, but the worst was during break when you would be grabbed by several boys and “Tapped” which involved getting your head struck under cold water tap while they chanted “and that’s for Flodden” or Andy, another battle which the Scots lost to England.

However, by and large, I have fond memories of Scotland. I made some very good friends and managed to get in some great experiences and skills.

I was shown how to “Guddle” and “Girn” for trout. Guddling involves lying on the side of a little stream or burn and sliding your hand under the bank against the water flow and gently getting your hand along the fish and then whipping it out on to the bank. Girning involves a bigger river (like the Leader which flowed in the private fishing grounds of the Thirlestane Castle). All that was required was a length of brass wire (used for snares) and a long pole. Tie a slip knot in the wire, tie it to the pole and walk in the river, going up stream. The river was fast flowing but relatively shallow and the trout tend to lie in pools, facing upstream. A slow approach and then pull the loop in the wire over the fish’s head and throw the pole, noose and fish out on the bank. I got a number of dinners that way, but the trick was not to be caught by the games keeper.

During the war the long summer holidays were split in two. The first half was a conventional summer holiday. The second half was delayed in Autumn as a “potato picking holiday”. As the name implies it entails going to a local farm growing potatoes (in our case, next door), being allocated about a 50ft stretch of the potato row and then waiting for the tractor pulling the potato digger to run down your row. The digger had a rotary set of tires at the back and would throw dirt, potatoes and stones into wide swash about 10ft wide in your 50ft section. They provided baskets and trick was to get the potatoes into the baskets before the tractor came back again. It was a frantic race, bent over all the time. However, they paid you by the hour and any income was a godsend. I can’t remember how much it was per hour though.

During the potato picking time they also had grain harvesting, essentially oats. We were not involved in the harvesting of the oats but in the harvesting of rabbits which thrived in the grain fields. Word would spread that there would be a “finishing” at a certain farm on a certain day and we would descend on the farm and set up a station on the outside of the field. The tractor, pulling the harvester, starts on the outside of the field and slowly starts to work in towards the center.

The rabbits, in the field first start to run towards the center but then realize they must get out and bolt outward. That’s when we used to get them, chasing them down and knocking them out with a stick. An old golf club with an iron head is ideal. I know it sounds cruel, but they used to destroy an awful amount of grain and the farmers were delighted to get rid of them. A friend of mine, Ian Forrest was extremely fast and could overtake a rabbit in a field. On a good finishing I might get 6 or 8 rabbits. They were a welcome addition to the rations. If memory serves, the meat ration for our person for one week was about 4ozs, (including kidney, liver and sausage), Mum served up the rabbits roasted, in a pie, or in a stew. Much appreciated.

My friend, Ian Forrest lived on a farm a few miles from Lander. The farm covered several square miles, much of it wild heather hills with many interspaced small woods. The shooting rights had been let out to a consortium of bigwigs from Edinburgh and they would descend some Saturdays for a day’s shooting. For this they needed beaters to beat up the game, which was pheasants, rabbits, partridge and the occasional snipe up on the moors.

It was wonderful opportunity to earn 7 shillings and sixpence (three half crowns) and a mullet pie (similar in size and shape to the ubiquitous Melton Mowbray pork pie you can buy in England now, about 3” in diameter, but still tasty).

The beaters also carried the game bags and retrieved the game. Some of the shooters were not very good and occasionally we got more rabbits with our sticks going through the woods than they did with the game that was flushed. I remember when Ian took 5 rabbits out of one hole in the ground.

My Mum found me a job in the local chemist shop, which also functioned as a post office. Five shilling a week, but unlimited access to a trove of National Graphics going back to the year dirt. I could take up to 2 at a time to read at home but had to return them to get another 2. I also delivered telegrams on the shop’s bike up to about a 7-8 mile radius of Lander.

I September of 1944, my Mum had a letter from her sister Lilly, to say that her boy, John, a few months older than me had enlisted in the army as a boy apprentice.

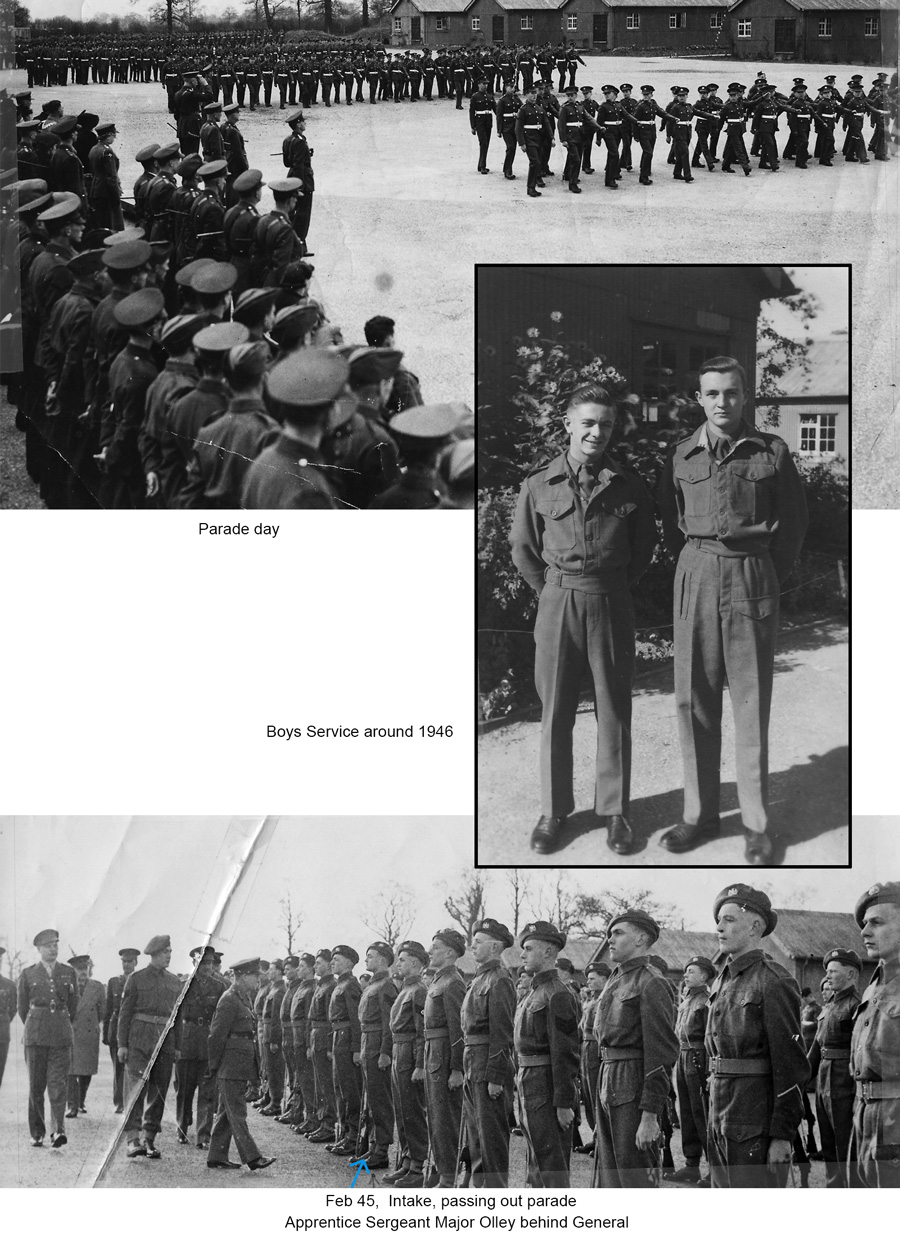

There were relatively few prospects in Lander so we decided to investigate. It turned out it was for boys 14 ½ to 15 ½ and there were a number of trades available. John had enlisted as a trainee armorer. I was interested in instrument mechanic. I had always been interested in small mechanisms and had repaired a number of clocks. With Mum’s blessing I went up to Edinburgh, took the exam and passed. In Feb 1945 (the war was still on) I met up with another lad called Scott and we made our way down to London and then to Wokingham, near Reading in Berkshire. We were met by truck and transferred to Arborfield where the school was established, I stayed for the next 3 years.

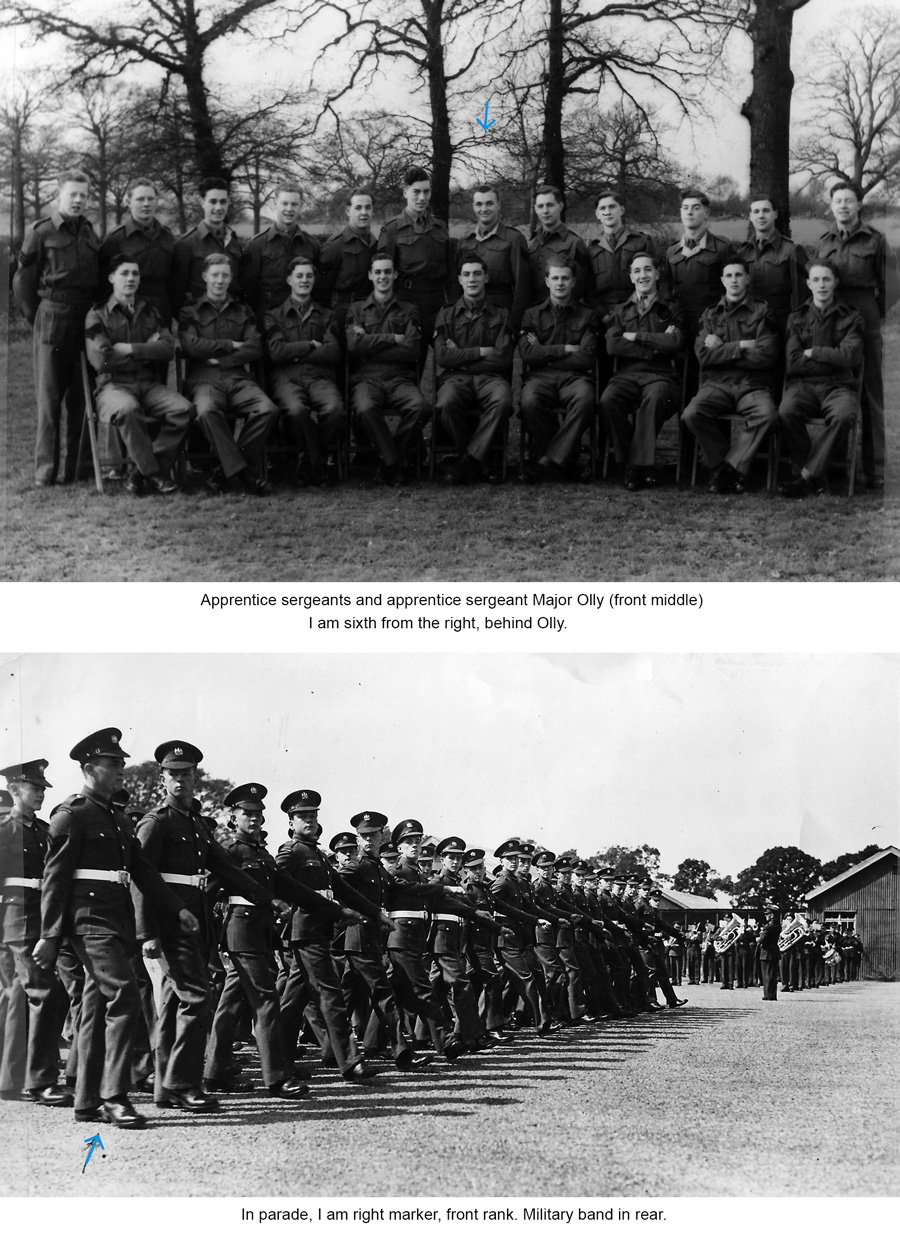

Thinking back on it, it was a wonderful learning experience. The first 3 months were purely military training. Drilling on the field until we started to look like soldiers.

The next six months were basic trade skills, such as fitting, sawing, drilling and then machines such as lathes, millers and shapers. We also learned welding, brazing, light smiting and black smiting. All great fun.

After this basic training we were split off into the primary trades and I spent many happy hours working on telescopes, binoculars, range finders, watches and clocks.

WWII finished in 1945, followed by the Japanese surrender and in Dec. 1945 my Dad was finally repatriated after being captured in Singapore, taken up north by cattle train and spent 3 years working on the Siam death railway. He went up country with, I believe about 130 men from his company but only about 27 survived. The delay in repatriation was caused by the severe malnutrition of the prisoners. They had to have special rations, in graded amounts to rehabilitate them. Dad was never over weight, but he was 6’2” and weighed on 96lbs.

During his captivity he had his front teeth knocked out by a rifle butt and survived dysentery, beriberi and other afflictions.

Though he did survive he was not a fit man and for several years was in and out of hospital.

He was initially stationed at Milldam Barracks in Portsmouth while they sorted through his demobilization. The biggest problem was where they would live. They knew that they would like to be near Milford-on-Sea, where his parents lived but needed some help in finding a house. To this end they applied to various small towns in the area for a council house. Like all council housing, there is always a waiting list. However, they had an offer from New Milton and finally had a place of their own on lower Ashley Road.

Unfortunately, the amoebic dysentery bug was well lodged in his liver and his eyes and skin were always yellow. His final hospitalization was in 1951 but when the operated they found he only had about one square inch of liver left. This was before liver transplants were available so all they did was sew him up and let him die. He was aged 51, taken too soon.

That was a quick digression from my boy’s service exposition, but it seemed a good point to add a little background about my Dad.

When I arrived at Arborfield, I was installed in “C” Company. There were four companies, A, B, C and D housed in barracks laid out in the form of a “spider”, ie. 6 barrack rooms arranged 3 per each side of a central bathroom, washroom, shower and toilet block, looking a bit like a spider. A and B companies were four spiders on the right side of the parade ground, C and D were on the left side.

The cookhouse/dining room were at the bottom of the square (parade ground). Each barrack room held about 24 beds, 12 each side, the beds themselves were made of steel with a wire mesh. The bottom half of the bed slid up into the top section and reassembled into a chair. We had 3 “biscuits” which were square “mattresses” about 2ft square, so 3 biscuits covered the whole bed. We had 4 blankets, 2 sheets and a pillow. Every day beds had to be made up arm chair fashion, with the 3 biscuits on top of each other and then a neat pile of 3 blankets, interweaving in the 2 sheets, all folded neatly and enclosed in the 4th blanket with the pillow on top. The rooms were inspected each day and any infraction or sloppy bed making were punished. The floors were wood and were swept out every morning and then the center of the room and the spaces between each bed had to be polished with a “bumper” (a padded block with a heavy metal weight on top and carried on a long pole. One thing they did provide was floor polish. Other wise we had to supply anything extra (excluding food and clothing). As boys we were paid 4 shillings per day, at 12 pence per shilling. In practice we were paid 4 shillings per week and the rest was kept back and given to us when we went on leave, Xmas, Easter and Summer. However, that had to pay for boot polish, blanco (khaki and white) for our webbing and white dress belt, writing paper, stamps, toothpaste, soap and if anything was left over, we’d buy “tea and a wad” down in the N.A.A.F.I in camp (Navy, Army and Air Force Institutions).

We were always hungry; the food has edible but a bit un-adventurous. You could fill up on potato and cabbage, but meat was minimal. The bread ration was 2 slices for breakfast and 2 for tea, but since the margarine was in one piece, a 1-inch square for each 2 slices of bread didn’t go far.

Once a month your platoon would be delegated for fatigues. After the morning parade at 8 am, while everyone else would march off, the fatigue platoon would be allocated. So many is the officer’s men, so many is the sergeant’s men, so many to the cookhouse while the remainder would be allocated to agriculture. During the war, most of the playing fields around the camp were converted to growing food which finally finished up in the cook houses. This camp had 2 shire cart horses, Bob and Gilbert.

I don’t know why but I always finished up on agriculture. Not that I minded, we were out in the fresh air and supervision was at a minimal. The only fly in the ointment was that agriculture was supervised by the Captain Quartermaster, a Ben Cook, ex guard and reputed to have the loudest voice in the British Army, when Ben shouted, everyone jumped.

The guardroom, at the camp’s front gate, was run by a Sargent Drainfield, a tyrant who made anyone on “jankers” (confined to barracks) a miserable hell. I always seem to get on ok with Ben Cook and I remember that we were at the far end of the camp, by the hospital and back gate and Ben, who also didn’t like Dransfield, would stand up, face the guard room (about a ½ mile away) and bellow “SARGENT DRANSFIELD”!!

Dransfield would run out of the guard room and squeak, “Sir” – Ben would then bellow “WHAT’S THE TIME”. Dransfield would look at the guardroom clock, get on his bike and peddle all the way up to Ben and tell him the time. Ben was always polite, but we knew that Dransfield was annoyed.

Another time, I was waiting for Ben and he comes up, sitting on Bob and with Gilbert walking behind. “GET ON THE ‘ORSE” bellows Ben. I look back at the monstrous beast, no saddle, no reins, I was petrified, however by grabbing the mane I finally got up on the horse. It was like riding a door, it was so wide.

Anyway, Ben gives a couple of clicks and off goes Bob, one more click and Gilbert follows and we head up to the far end of the camp where there was a gate. “OPEN THE GATE” bellows Ben and I slid off Gilbert, hit the ground and immediately hit by cramps in both legs. So there I am, looking like a frog. Ben doesn’t even crack a smile, “OPEN THE GATE” he bellows again. In sheer terror I hopped like a frog to the gate, unlatching it, Ben goes through with the two horses, and I finally can stand up and follow him through. I never went up on Gilbert again and walked from then on. In honesty I can say that I have never been on a horse since.

However, Ben could be very kind and I remember one weekend afternoon we (a couple of us) had walked down to Wokingham, the nearest town. I should point out that we were originally walking to the Army Technical School, and we had brass letters on our uniforms “ATS”. Unfortunately, during the war, the army recruited woman and girls into the Auxiliary Territorial Services, also known as the ATS (it subsequently became the Women’s Royal Army Corps) or WRAC for short and even the present Queen Elizabeth served in its ranks.

However, the local cabbies in Wokingham liked to poke fun at the ATS boys, calling them “girls” and that led to some bloody fisticuffs and in due course our school became the Army Apprentices School or AAS for short.

Anyway, I am digressing. It was in this later, peaceful time that we were just approaching the guardroom when we heard Ben bellow, “YOU BOYS COME HERE”. We never knew that he and his family lived in a cottage, just outside the main gate.

We frantically rushed over to the gate of the cottage, quickly checking our uniforms to check if we were improperly dressed a moment later we were lined up outside Ben’s garden gate, standing to attention and wondering what we’ve done. However, Ben bellowed, “DO YOU LIKE APPLES”? We nodded yes and he beckoned us in and showed us a big box full of apples. “TAKE THEM AWAY” says Ben – we gasped our thanks and then started off to the front gate – where we were met by Sgt. Dransfield. “Have you been stealing apples” says Dransfield – “no” we gasp, “Captain Cook gave them to us” “A likely story” says Dransfield – and at that his staff comes out of the guard room and they take half the apples.

However, we still had plenty to share with our roommates afterwards.

There were 2 intakes each year, if February and September. I enlisted in the Feb 1945 intake. For the first 6 months we were called “Jeeps” and the lows were picked on by every senior intake and we dreaded the time just before the next passing out parade because the 18 year olds who would be leaving in the next week would descend on the barrack rooms, after lights out (10 pm) and cause chaos. The favorite was to grab the end of the bed and lift it up vertically. At which point the bottom half of the bed would slide into the top section and you would slide into the top section and you would be lying in the middle of a great tangle of biscuits, blankets, sheets and pillows.

Sometimes they’ll get really inventive and I remember we had one, very small boy called Titch Rowell, no more than 5ft high. We had steel lockers on the wall just over the bed for all of our kits. They pulled his kit out of the top section, folded him up and stuffed him into his locker. Poor lad, he couldn’t move, we had a dickens of a job getting him out in one piece.

We had three bands in the school, a Military, Scottish pipe band and the Drum and Fife, affectionally known as the Spit and Dribbles.

Sunday morning was always a Church Parade in the morning, with a march past. On Saturday and Sunday afternoons you were free to leave camp (if you wanted to) but in full uniform, of course. As you didn’t have to make your bed up Sunday, it was a nice time to snooze.

In October 1947 I reached 18 and my regular army service theoretically started. Initially I was enlisted in the GSC (General Service Corps) but carried on at the school until February 1988 when we had our passing out parade. Mum and Dad came up for the occasion and I was awarded the trade prize (a book on watch repairing which I still have).

After passing out we were allocated to our different camps. In my case if was the Royal Electrical and Mechanical Engineers (REME for short) and we were passed out to the different training battalions to be taught the specialized skills which you might need, much on vehicle driving (motorcycles, 1 ton and 3-ton trucks) Setting up a workshop in the field, recovery of disabled vehicles and the extent of R.E.M.E Installations.

R.E.M.E has base workshops where major strip down and repairs are done, command workshops which handle all repairs short of a complete strip down and L.A.Ds (Light Aide Detachments) which are small assemblies of tradesmen, up to about 130 men which are attached to regiment to handle all small repairs to the regiments equipment. Thus, for example, my first posting was to a command workshop (21 command), as a Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the Royal Artillery.

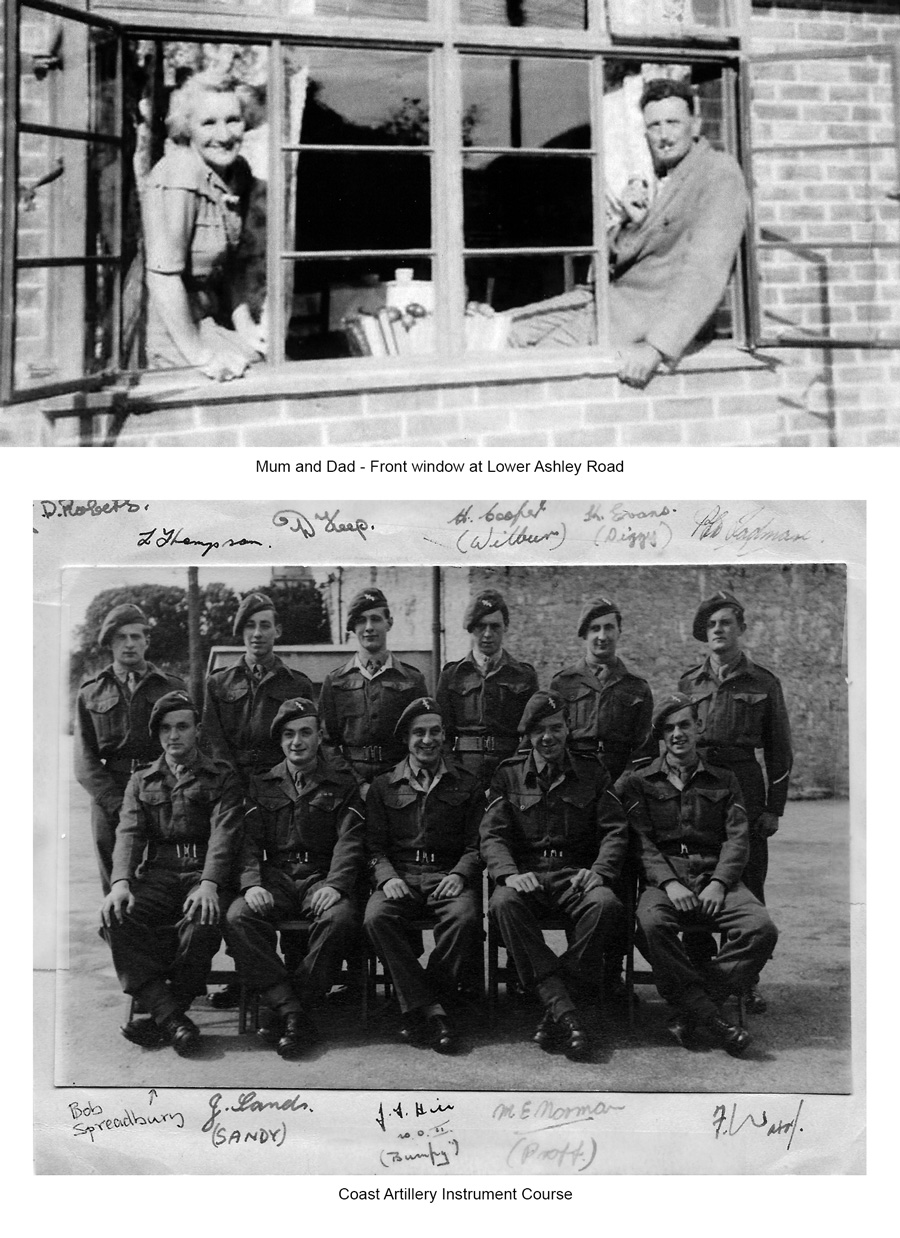

During this compressed training in instrument mechanics we were sent on coast artillery instrument courses. One of these was at the Citadel in Plymouth, Devon. When Drake finished his game of bowls before setting off to defeat the Spanish Armada. This was a great services station, as it is one of the depots of the Royal Navy, so there was plenty of service places to see and enjoy.

At the end of this training session we were finally posted to our first stations in R.E.M.E. I was sent to the 21 Command Workshops in Burscough, Lancashire, about 20 miles north of Liverpool. That was a fun time in my trade from 3 to 2 to 1 and I was promoted to Lance Corporal, then to Corporal and finally to Sargent.

While as a Corporal I used to go out to all of the Army establishments in our command area to do inspections of all of the instruments, do small repairs and otherwise arrange for them to be sent back to the workshop for major repairs.

I also had a memory quality experience. The workshop was very close to a railway station on the main line to Liverpool and the main gate to the camp was staffed, during the day, by civilian guards. However, from 6 pm to 7 am, the military provided a guard of one Corporal and six men. The Corporal stayed up all night and changed the guard, both every 2 hours, to give 2 hours on and 4 hours off.

When we were relieved. We got breakfast and the men went off into the workshops while the Guard Command could sleep until midday but was then expected to report to the workshops. A great idea, except, for a while, there were only 2 Corporals, me and one other. After three weeks of this we were walking zombies until the upper brass realized what was going on and started making the Sargent’s do it as well.

One other job I remembered was at the Easter weekend, in 1949., when I was detailed to take 2 men down to Liverpool. We were informed that we had to collect 2 prisoners off a troopship that had just arrived from Egypt. Apparently the two prisoners had been court martialed for steeling Army equipment and selling it to the Arabs. They had been sentenced to military prison in England.

On Good Friday we were trucked down to the docks, collected the prisoners, they were handcuffed to my two lads and brought back to the barracks where the two prisoners were placed in a cell in the guardroom and we were free until Sunday evening. At that time we collected the prisoners and were transported to the main line station and were locked into a compartment, by ourselves, by the station staff and set off, just after midnight for the number one Army prison, known as the “Glasshouse”, in the small Somerset village of Shepton Mallet. We arrived there about seven in the morning and as it was close to the station, walked down to it. A forbiddingly grim place, high walls and a large wooden gate, with a small door set in to it. By this time our two prisoners were shaking in their boots and we were not much better.

I banged on the little door and a small window opened. A quick question from the gate, my reply, “two prisoners and escort”. At this point, the small door opened, two more guards appeared, my lads and the prisoners were whisked inside, the handcuffs were off, and my 2 lads were shot back out and the door closed, we could hear the two prisoners being screamed at and they were off at the double. We had, had no breakfast but neither my 2 lads nor I fancied hanging around, so we went back to the station to wait for the next train back.

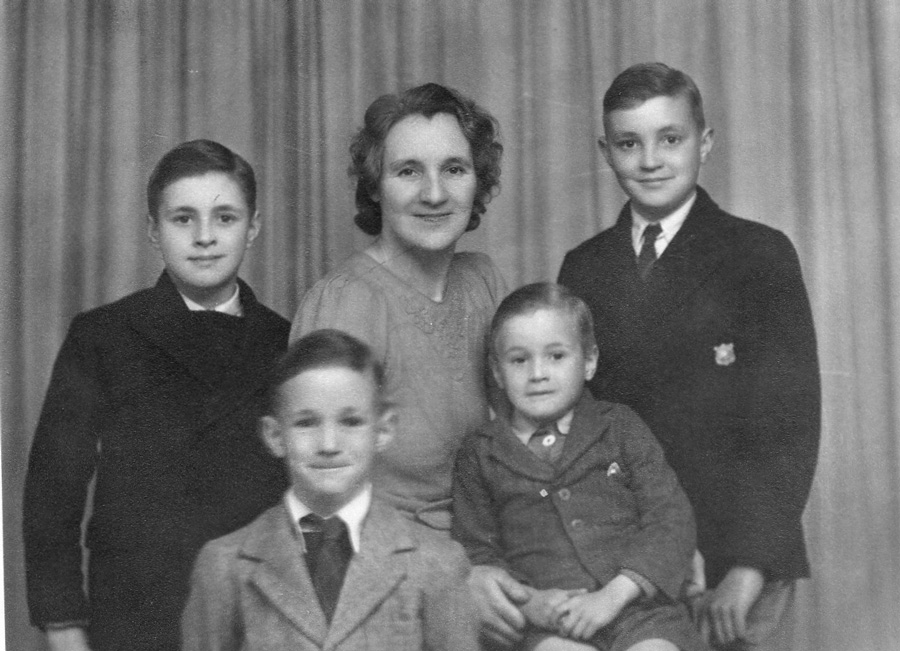

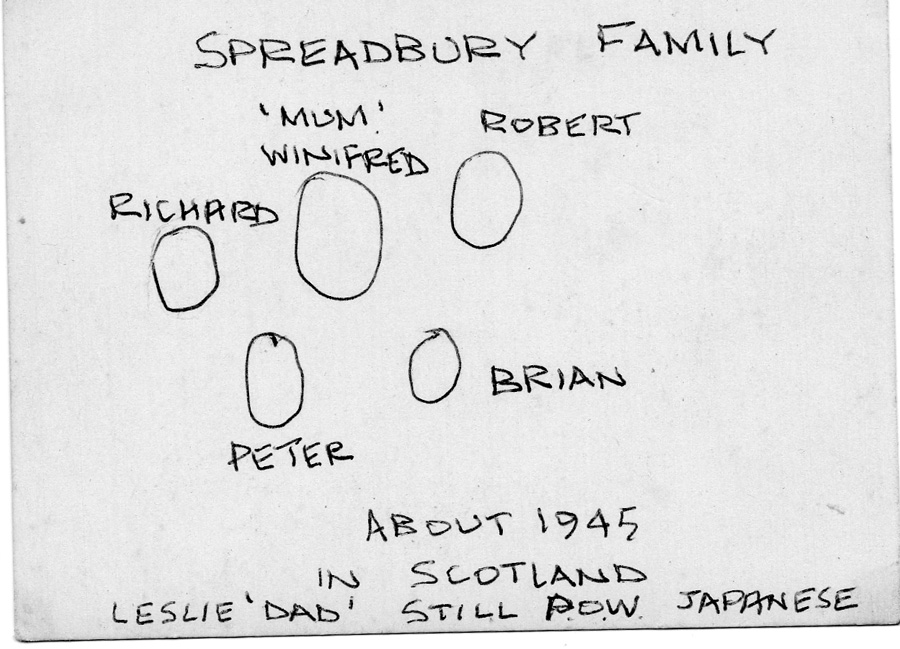

From left to Right - Richard, Peter, Mother Winifred, Brian and Bob (1945)

1940 -1949